What is toxic stress and why does it matter for youth mentoring programs

By Venessa Marks and Julie Novak

This blog is part of a three-post series on toxic stress.

The first post explains what toxic stress is and why it matters for youth mentoring programs, the second highlights what professional staff need to know about toxic stress, and the third discusses recent programmatic innovations related to toxic stress and trauma-sensitive care.

________________________________________

Emerging research on brain development is shedding new light on how and why our childhood experiences impact the adults we later become. Studies have shown that severe and pervasive negative experiences during childhood– those that elicit a toxic stress response – can actually impact the developing architecture of the brain and the functioning of the immune system.[1] When children do not have adequate adult support to help buffer the impact of severe stressors, they often later face significant behavioral challenges and health risks as adolescents and adults. Youth mentoring programs have an important role to play in building resilience in youth – offering hope through promoting healing and building protective factors. Mentoring programs may achieve greater success in working with vulnerable children and families by ensuring that programs provide staff, volunteers, and parents opportunities for training that help prepare them to respond appropriately to the cognitive and behavioral challenges often associated with toxic stress.

What is toxic stress?

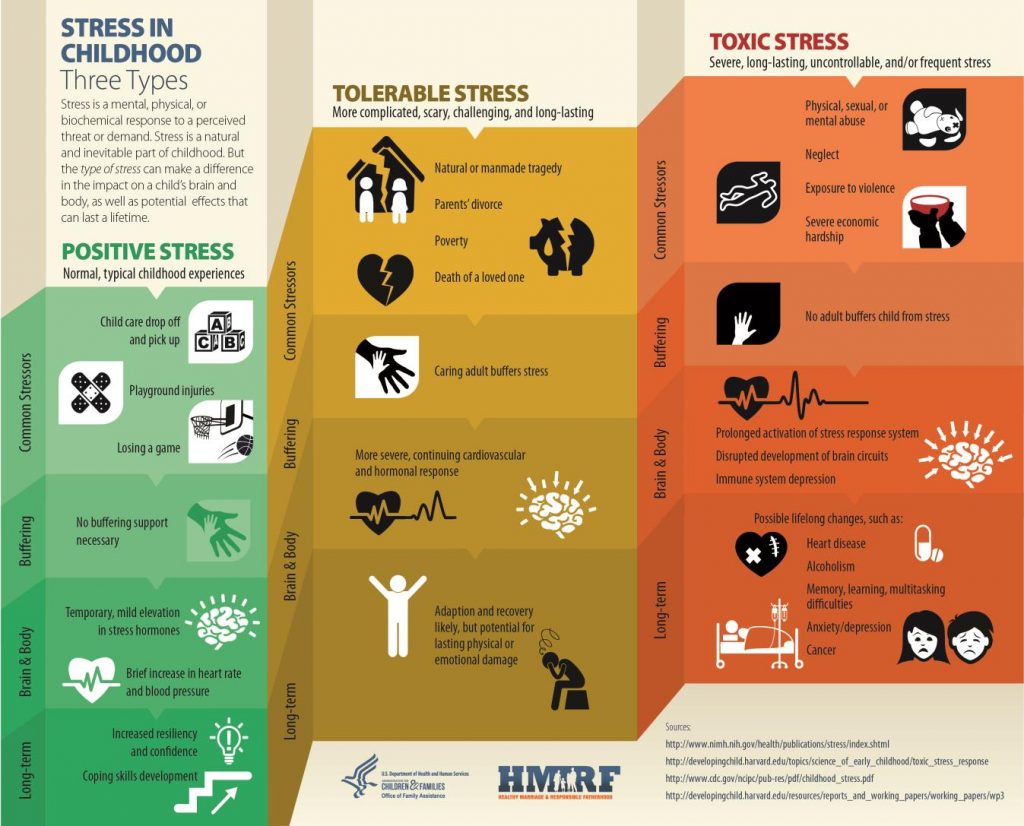

Stress is a subjective, biochemical response to a perceived threat or demand. When we experience stress, specific hormones are released in our brain and our heart rate elevates in preparation for a ‘fight or flight’ response.[2] As depicted in the diagram below, stress is a natural and inevitable part of childhood, but the type of stress can make a difference in the developing mind and body. Experiences that elicit a so-called ‘positive stress response’ – such as starting daycare or losing a game – can build confidence and character. Tolerable stressors – such as a family divorce, the death of a loved one, or experiencing an illness – elicit a strong stress response that may last for an extended time period. With caring, consistent adult support, however, most children can recover from these experiences without lasting ramifications.

Toxic stress differs from tolerable stress in two ways. One, stressors that engender toxic stress responses tend to be very severe, frequent or long-lasting. These could include traumatic experiences such as physical, emotional or sexual abuse, exposure to violence at home, in school, or in the community, persistent poverty, homelessness, or neglect. Two, toxic stress responses are likely to occur when a child goes through severe or pervasive traumatic experiences that are not buffered by the presence of a loving, caring adult. That buffer can be provided by a parent, grandparent, or even a formal or informal mentor.

Source: Healthy Marriage & Responsible Fatherhood Training and Technical Assistance Center[3]

The elevated and frequent activation of the stress response can have a significant and long-lasting negative impact on a child’s developing brain and hormonal and immunological systems. For instance, toxic stress can impair the development of the limbic system in the brain – the part of the brain responsible for emotional regulation, cognitive processing, and memory.[4] Youth and adults exposed to toxic stress as children can have trouble maintaining focus, processing and following verbal instructions, setting goals and problem solving.[5] Emotionally, they are more likely to struggle with anxiety, anger and depression and may have trouble recognizing and regulating their own emotional responses, or forming attachments to caregivers and others.[6] Toxic stress can also reduce one’s self-control, or the ability to set priorities and resist impulsive actions.[7]

These cognitive and emotional challenges often lead to challenges in the classroom and high-risk behaviors, such as substance abuse, overeating, or other types of risk-taking that can impact one’s long-term health and well-being.[8] Traumatic experiences (which may or may not elicit a toxic stress response as detailed above) can also lead to behaviors that are considered negative by adults and/or other youth (e.g. provoking fights, difficulty getting along with siblings or classmates, unresponsiveness to affection, inattentiveness in school, or unrealistic fears). These behaviors are actually natural consequences of the child’s experience and in fact may have helped them cope with the trauma or its after-effects. It’s important that the adults providing support to these children have an understanding of what a child has been through so that they can be empathetic even when the child is displaying negative behaviors. Further, supportive adults need to have realistic expectations and the appropriate training to shape their response to children’s behaviors. Experts say that “children who’ve experienced trauma need nurturance, stability, predictability, understanding and support.”[9]

Although the brain research on trauma and toxic stress is heart-breaking in many ways, there is also hopeful news presented in the research. Although children’s brains are altered by exposure to toxic stress, the research also shows that with the right interventions — through caring adult support and improved living environments that alleviate the stressors – brain development and functioning can and will improve.[10]

What are mentoring programs positioned to do about trauma and toxic stress?

Mentoring programs are serving individuals every day who have been exposed to violence, trauma, or even toxic stress. We are working with parents and caregivers who have struggled with – and have often shown remarkable resilience in the face of persistent poverty, loss, and abuse. And of course we are serving children who may be coping with the ongoing or residual effects of toxic stress. We have a responsibility to serve these families and children with competence and compassion…but what does that look like? Here are a few ideas for how mentoring programs can leverage the latest research in brain develop, trauma, and toxic stress to improve their services:

- Educate your staff. There are a number of free resources and webinar series available online targeting frontline staff serving vulnerable populations. See the resource list below for a few suggestions. If you have the funding or relationships, consider partnering with clinical professionals or university researchers in your community to train and support your staff as they become more trauma-sensitive. Reach out to your local Department of Child and Family Services, your local schools, and child advocacy centers to learn about their efforts in integrating trauma-sensitive practices into their models and explore opportunities for partnership in training and education. Be mindful that your staff members might have a history of trauma or toxic stress themselves – instruct any trainers or partners to be sensitive to this possibility, and to focus on hope and healing in their presentations.

- Be careful and conscientious while matching. Conduct a thorough enrollment interview with children and their families to learn about any exposure the child and/or their family may have had to past trauma, to better understand possible causal factors for a child’s delayed development and/or behaviors that may be outside the norm. Take this information into account when matching, ensuring that children with a history of trauma exposure are matched with your most committed, mature, experienced and consistent mentors who are open to training in working with trauma-exposed youth.

- Develop formal referral networks. A more extensive screening process during intake may bring to light additional family or youth challenges. Be prepared to address those issues early and continuously through formal partnerships with complementary service providers. Carefully select referral partners, ensuring the services are trauma-sensitive and culturally responsive.

- Maintain strict child safety standards. Ensure that your programs meet strict safety best-practice standards that place top priority on child well-being and prohibit all forms of abusive behaviors on the part of volunteers and staff – including use of demeaning language, shaming, and harsh treatment or punishment. Train everyone associated with your organization – professional staff, volunteers, parents and children – on child abuse prevention, mandatory reporting and inappropriate behaviors that may indicate a child’s emotional or physical well-being is threatened.

The emerging research on toxic stress and its impact on both adult and child behavior and functioning is extremely relevant for mentoring programs seeking to engage families and build resilience in young people. Toxic stress and trauma-sensitive practices can, in fact, benefit all populations, but are particularly crucial for our most vulnerable clients.

Suggested Resources:

- The Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University. This website offers free articles, online trainings and information about the latest research on brain development and toxic stress: http://developingchild.harvard.edu/

- “Enhancing and Practicing Executive Function Skills with Children from Infancy to Adolescence.” This article provides activity suggestions that could inform match activities for children with impaired executive functioning skills (self-control, working memory, emotional regulation): http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/tools_and_guides/enhancing_and_practicing_executive_function_skills_with_children/.

- “Toxic Stress in Low-Income Families.” This recorded webinar features an expert panel explaining toxic stress and what practitioners are doing to prevent toxic stress exposure in children and ameliorate its effects on adults: https://hmrf.acf.hhs.gov/articles/toxic-stress-in-low-income-families/#.Vh6koflVhBd.

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. This website provides helpful information on trauma-sensitive care and vicarious trauma for staff: http://www.nctsn.org/.

- “Using Brain Science to Design New Pathways out of Poverty.” This article, written by a service provider, offers concrete tips and examples of how direct service programs can change their operating procedures and processes to make them more accessible and successful for adults with impaired executive functioning skills: http://www.liveworkthrive.org/site/assets/Using%20Brain%20Science%20to%20Create%20Pathways%20Out%20of%20Poverty%20FINAL%20online.pdf.

- “Understanding the Effects of Maltreatment on Brain Development.” This resource provides a more detailed explanation of brain development and the impact of childhood trauma and toxic stress: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/issue-briefs/brain-development/.

- “The Elements of Effective Practice for Mentoring – 4th Edition.” This resource suggests evidence-based standards for mentoring, including child safety and screening standards: http://www.mentoring.org/program_resources/elements_and_toolkits.

- “Preventing Child Sexual Abuse Within Youth-Serving Organizations: Getting Started on Policies and Procedures.” Created through a collaboration of violence prevention researchers and child safety experts from some of the nation’s largest, most experienced youth-serving organizations, this guide provides a framework for organizations to assess and strengthen their child abuse prevention efforts: cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pub/preventingchildabuse.html.

- Commit to Kids. This program from the Canadian Centre for Child Protection provides a step-by-step guide to help organizations create safe environments that protect children from misconduct and abuse within youth-serving organizations: commit2kids.ca.

As a Senior Manager with ICF International’s Family Self-Sufficiency team, Venessa Marks specializes in supporting and evaluating community-based workforce development initiatives for vulnerable populations. As the former Vice President of Research, Innovation and Growth for Big Brothers Big Sisters of America, Venessa worked with the BBBS network, national leadership, and valued partners to set BBBSA’s research agenda and to invest in innovative, impactful programming. As the Vice President of Strategic Partnerships for New York Needs You, Venessa created and launched their corporate giving and volunteer engagement department. Later, as their Vice President of the Fellows Program, Venessa ran the organization’s signature mentoring and career development program for first-generation college students, leading programmatic evaluation and driving continuous, data-driven improvement. As a Director and Consultant with Dare Mighty Things, Venessa led training and technical assistance contracts supporting federal grant programs focused on positive youth development and nonprofit capacity building. Venessa earned a Master’s degree from the University of Chicago and a Bachelor’s degree from Pitzer College, studying social change movements. Venessa lives with her husband and daughter in New York City.

Julie Novak serves as Big Brothers Big Sisters of America’s leading expert and national spokesperson on child safety and youth protection-related matters. She leads the nationwide advancement of effective child abuse prevention and crisis response strategies throughout Big Brothers Big Sisters’ network of more than 300 affiliates, working collaboratively with other national experts. Novak develops and provides statewide and national child abuse, violence prevention and crisis management training and consultation reaching thousands of professionals, volunteers, parents and children every year. She’s served as a member of: the National Coalition to Prevent Child Sexual Abuse & Exploitation, the U.S. Olympic Committee’s Safe Sport Working Group, Vice President Biden’s Gun Violence Task Force, LexisNexis/First Advantage’ Customer Advisory Board, and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children’s Safe to Compete Working Group.

Prior to coming to Big Brothers Big Sisters of America, she served as CEO of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Northwestern Wisconsin for 11 years where she secured and administered collaborative local, statewide and federal violence prevention initiatives working with the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Wisconsin Department of Justice, the Department of Human Services, and local law enforcement. She’s served as an Executive Committee Member of the Eau Claire YMCA, President of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Wisconsin, a founding board member of the Boys and Girls Club of the Greater Chippewa Valley, and as Nationwide Leadership Council Vice-Chair, Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. After graduating from the University of Iowa she served for three years as a Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Victims’ Advocate. She resides in Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

[1] Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., & McEwen, B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301, 2252-2259.

[2] De Bellis MD. The Psychobiology of Neglect. Child Maltreatment. 2005; 10:150–172. Dozier M, Peloso E, Lindhiem O, Gordon K, Manni M, Sepulveda S, et al. Developing evidence-based interventions for foster children: An example of a randomized clinical trial with infants and toddlers. Journal of Social Issues. 2006;62:767–785.

[3] Also reproduced in: Hyra, Allison; Kendell, Jessie (2015). Translating the Science of Childhood Stress into Youth Service Practice. Youth Today.

[4] Shonkoff et al., 2009

[5] Child Welfare Information Gateway (2015). Understanding the effects of maltreatment on brain development. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau.

[6] Walkley, M & Cox, L. (2013). Building Trauma-informed schools and communities. Children & Schools. Vol. 35(2), p123-126; Child Welfare Information Gateway (2015).

[7] Child Welfare Information Gateway (2015).

[8] Arruabarrena, I., & Paul, D. (2012). Improving accuracy and consistency in child maltreatment severity assessment in child protection services in Spain: New set of criteria to help caseworkers in substantiation decisions. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 666-674.; Middlebrooks JS, Audage NC. (2008). The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta, GA.

[9] American Academy of Pediatrics. (2000). Committee on Early Childhood and Adoption and Dependent Care. Developmental issues for young children in foster care.

[10] Child Welfare Information Gateway (2015).