Parents Aren’t Teachers — They’re Parents

Kent Pekel

Kent Pekel

President and CEO, Search Institute

At the start of the current school year, I was struck by the number of superintendents, principals, and other educational leaders across the country who called on parents to get more involved in their children’s learning. I also noted that many of them promised to make family engagement a key component of their efforts to support students and improve schools.

But now that the time for parent-teacher conferences has arrived and parent advisory committees are beginning their work, I bet that in many schools it is only the usual suspects who are showing up. As a former classroom teacher who, despite my best efforts, experienced low levels of parent involvement, I know it’s tempting to interpret this tepid response as evidence that most parents are not deeply concerned about their children’s education. But the work that I am now doing at the nonprofit research organization Search Institute has led me to believe that a different, more important, dynamic is at work.

As educators, we often emphasize the wrong things when we urge parental involvement. Rather than asking parents to reinforce what we do in schools, we need to find ways to reinforce what parents can do to be effective parents.

Most family engagement efforts focus on getting parents to help with homework or to participate in a range of activities at school. For example, the U.S. Department of Education tracks parent involvement based primarily on the following indicators: did parents meet with their child’s teacher, attend a general school meeting, volunteer at the school, serve on a committee, or attend a school event at least once during the school year.

All of those are potentially valuable endeavors, but many parenting adults don’t have the time, skills, or desire to serve as their children’s first teachers or to help improve the curriculum or climate in their schools. In contrast, almost all parents are ready, willing and able to influence something that really matters to their children’s success: the quality of their family relationships.

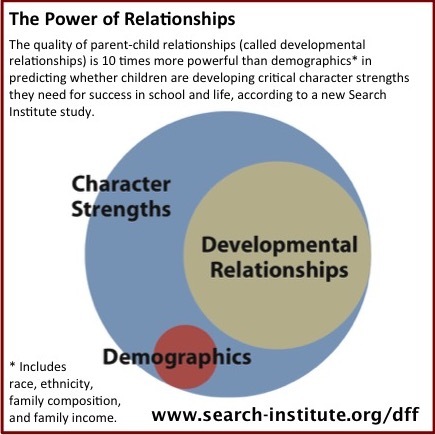

It is not particularly novel to say that parent-child relationships matter, but it is new to suggest that schools should help families strengthen them. Evidence for adopting that approach comes from a just-released Search Institute study, Don’t Forget the Families. Based on a national survey of a diverse sample of 1,085 parents of 3 to 13 year olds, our research underscores the powerful role that parent-child relationships play in children’s learning and development.

When parenting adults (including foster parents, stepparents and others) reported building relationships with children that feature high levels of five actions, they were also significantly more likely to report that their children have developed key character strengths, including perseverance, conscientiousness, self-control, and the ability to work well with others. A growing body of research demonstrates that such character strengths are as influential as IQ in determining life outcomes not only in school, but also in the workplace, and in areas such as health and criminality.

The five relational actions that our study finds positively influence young people’s social and emotional development are: expressing care (showing the child that you like and want the best for him or her), challenging growth (helping the child continuously improve and stretch), providing support (helping the child complete tasks and achieve goals), sharing power (hearing the child’s voice and letting him or her share in making decisions), and expanding possibility (broadening the child’s horizons and connecting him or her to new people and opportunities).

Our study shows that the degree to which children experience these relational actions in their families is ten times more predictive of their development of key character strengths than demographic factors such as income, race or ethnicity and family structure. At a time when much of our national discussion about young people seems to suggest that demography is destiny, that is a hopeful finding.

Our study also finds that parents from all backgrounds are very interested in receiving support that helps them strengthen family relationships. There are many ways that schools could begin to provide that support. Some are simple, such as sharing tips for building strong relationships at parent-teacher conferences and school events. For example, a number of the children and teenagers who participated in focus groups we conducted for our study told us about times when an adult learned that they were struggling with something and then periodically checked in to see how things were going. Because the adult did not wait for the young person to bring the issue up again or for circumstances to prompt or force another discussion, the young person felt powerfully seen and deeply supported. The act of proactively checking in on a challenge might sound obvious to some, but the young people who told us that action is influential also told us that it is relatively rare.

Some schools will want to go beyond providing simple tips to launch more ambitious efforts to help families strengthen developmental relationships. For example, at Search Institute we are working with a group of middle schools that are helping parents understand and apply research on motivation and academic mindsets. We are finding that providing parents with tools and techniques that help their children view intelligence as something that can grow with effort not only increases motivation at school, but also strengthens relationships at home.

The vast majority of American children spend only about 15 percent of their time in school from kindergarten through 12th grade. If we are to influence the other 85 percent, we must find new ways to engage parents in the effort. Parenting adults from all backgrounds have the capacity and the desire to build developmental relationships with their children, and the evidence suggests that helping them do that more intentionally and effectively would do much to help their children succeed in school and in life.

Follow Kent Pekel on Twitter: www.twitter.com/KentPekel