How mentoring is suited to developing passions: More about nurturing a spark than finding a flame

Posted by Melissa De Witte, futurity.org

Posted by Melissa De Witte, futurity.org

The advice to “find your passion” might undermine how interests actually develop, according to new research.

In a series of laboratory studies, researchers examined beliefs that may lead people to succeed or fail at developing their interests.

Mantras like “find your passion” carry hidden implications, the researchers say. They imply that once an interest resonates, pursuing it will be easy. But, the researchers found that when people encounter inevitable challenges, that mindset makes it more likely people will surrender their newfound interest.

And the idea that passions are found fully formed implies that the number of interests a person has is limited. That can cause people to narrow their focus and neglect other areas.

Fixed mindsets

To better understand how people approach their talents and abilities, the researchers began with prior research from Carol Dweck, a professor of psychology at Stanford University who also contributed to the new work, on fixed versus growth mindsets about intelligence. When children and adults believe that intelligence is fixed—you either have it or you don’t—they can be less resilient to challenges in school.

Here, the researchers looked at mindsets about interests: Are interests fixed qualities that are inherently there, just waiting to be discovered? Or are interests qualities that take time and effort to develop?

To test how these different belief systems influence the way people hone their interests, the researchers conducted a series of five experiments involving 470 participants.

In the first set of experiments, the researchers recruited a group of students who identified either as “techie” or a “fuzzy”—Stanford vernacular to describe students interested in STEM topics (techie) versus the arts and humanities (fuzzy). The researchers had both groups of students read two articles, one tech-related and the other related to the humanities.

They found that students who held a fixed mindset about interests were less open to an article that was outside their interest area.

A fixed view may be problematic, says Gregory Walton, an associate professor of psychology at the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford. Being narrowly focused on one area could prevent individuals from developing knowledge in other areas that could be important to their field at a later time, he says.

“Many advances in sciences and business happen when people bring different fields together, when people see novel connections between fields that maybe hadn’t been seen before,” he says.

“In an increasingly interdisciplinary world, a growth mindset can potentially lead to this type of innovation, such as seeing how the arts and sciences can be fused,” adds Paul O’Keefe, who was a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford, and is now an assistant professor of psychology at Yale-National University of Singapore College.

“If you are overly narrow and committed to one area, that could prevent you from developing interests and expertise that you need to do that bridging work,” Walton says.

Not interested

The research also found that a fixed mindset can even discourage people from developing in their own interest area.

In another experiment, the researchers piqued students’ interest by showing them an engaging video about black holes and the origin of the universe. The video fascinated most students.

But, then, after reading a challenging scientific article on the same topic, students’ excitement dissipated within minutes. The researchers found that the drop was greatest for students with a fixed mindset about interests.

This can lead people to discount an interest when it becomes too challenging.

“Difficulty may have signaled that it was not their interest after all,” the researchers write. “Taken together, those endorsing a growth theory may have more realistic beliefs about the pursuit of interests, which may help them sustain engagement as material becomes more complex and challenging.”

Developing passions

The authors suggest that “develop your passion” is more fitting advice.

“If you look at something and think, ‘that seems interesting, that could be an area I could make a contribution in,’ you then invest yourself in it,” says Walton. “You take some time to do it, you encounter challenges, over time you build that commitment.”

Dweck notes: “My undergraduates, at first, get all starry-eyed about the idea of finding their passion, but over time they get far more excited about developing their passion and seeing it through. They come to understand that that’s how they and their futures will be shaped and how they will ultimately make their contributions.”

The Bottom Line for Mentors and Programs

The studies discussed above point to a task for which mentors are uniquely suited: helping mentees to develop their passions and interests.

But what would that look like in practice? For mentoring programs, it could consist of building in a growth mindset into the training mentors receive before they are matched as well as the feedback and support provided to mentors throughout the duration of the match. That is, the process of developing interests could be framed as a part of the relationship-building process.

For example, let’s say a mentee has a general interest in technology, but not clearly-defined passions. That interest in technology could be seen as a jumping-off point for the mentor, including guiding activities the pair does together (e.g. building simple robots, learning about programming). This helps to build the relationship and the mentee’s interests and skills at the same time. The mentor might even learn a thing or two.

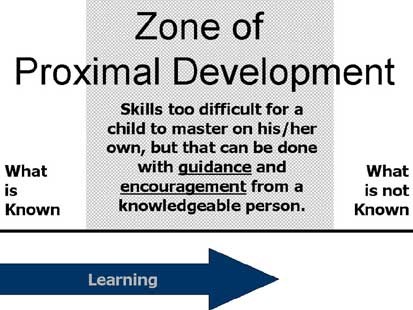

For mentors, their role could exist in what social and developmental psychologists term the “Zone of Proximal Development”, or “ZPD” for short.

Lev Vygotsky, a social psychologist, defined the ZPD as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978).

For a more visual representation:

In other words, by serving as a bridge between the known and unknown regarding a topic of interest, mentors can help their mentee navigate the distance between what they know of their interest and what they would like to learn.

Using the example of the tech-interested mentee above, this would mean that mentors begin by selecting activities that may be somewhat challenging, but are achievable. Learning about coding? Better to start with a simplified introduction to the concepts, rather than jumping directly to the differences between C++ and MATLAB. You may get there eventually, but the ZPD is more about supported stretches for the mentee than immediate understanding and mastery.

For mentors, it can sometimes be less about trying to discover a subject or activity in which their mentee already has an established love, but identifying those nascent areas of interest that the mentee may have and joining them in the process of developing their interest into a passion.

One other important point to consider here, as alluded to by Dweck above, is that developing passions is a long and, sometimes, challenging process. It rarely occurs in a linear fashion. By providing support, mentors can help their mentees continue to pursue their interests when they may have otherwise given up if left unsupported.

In adopting a developmental understanding of the concept of our interests, mentors and mentoring programs not only help their mentees build skills and curiosity, as well as foster creativity, but do so in a way that promotes the long-term success of their mentees.

To access the original research article, click here.