Finding Solutions to Support Child Care during COVID-19

By Gina Adams, Reprinted from Urban Institute

The title of this blog post was changed to reflect that the suggested child care supports are not limited to center-based care (updated 9/23/2020).

Families’ child care decisions vary based on their budgets, needs, constraints, and preferences. But COVID-19 has upended all these variables and has affected the supply of child care many families relied on before the pandemic. To support working parents as they balance the need to financially support their families with the desire to protect their children’s health, safety, and development, policymakers should consider ways to ensure families have access to a sufficient supply of child care options to meet their changing needs.

Returning to prepandemic child care arrangements is not be feasible for all families. Colleagues at the University of Oregon reported that lower-income families were more uncertain than higher-income families about their ability to return to their prepandemic child care arrangements as the economy reopens, with almost half (48 percent) of lower-income households reporting that they either couldn’t return or were uncertain they could, compared with only a quarter of higher-income households.

These data come from a survey from the University of Oregon’s Center on Translational Neuroscience. The Rapid Assessment of Pandemic Impact on Development (RAPID) – Early Childhood Survey was designed to continuously gather information regarding the needs, health-promoting behaviors, and well-being of families with young children during the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States.

Type of care

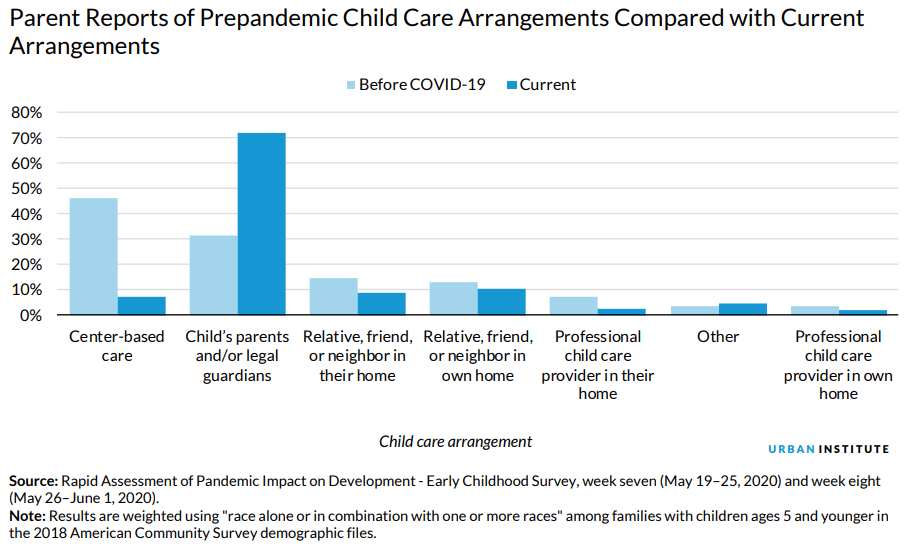

One explanation for the doubts that parents expressed about returning to prepandemic arrangements can be found by looking more deeply at the data. Specifically, data from the RAPID-EC survey show families who used center-based care before the pandemic reported the biggest reductions in use, falling from 46 percent to only 7 percent as of late May. There are many reasons for this, including that child care centers were more likely to close during the pandemic because of the restrictions on having large numbers of children in one space and challenges protecting children and staff.

As the pandemic continues, however, it appears there may be a shift in the kinds of care parents are using if they are using any nonparental care. Specifically, emerging reports suggest some families may be moving from center- to home-based programs.

There are two possible reasons for this trend.

First, some parents may be changing to home-based settings and caregivers to reduce health risks (given smaller group sizes), take advantage of more flexible schedules, or enroll their children in programs that are more affordable and closer to home or that involve care by people they know and trust.

Yet families wanting home-based options, particularly those needing financial assistance to pay for it, may find it difficult. Licensed family child care programs have been on the decline (PDF) across the country for many years and have been hard hit by the pandemic. And families who want to use home-based options that are legally exempt from licensing—usually family, friend, and neighbor caregivers and smaller family child care homes (PDF) in some states —may find it difficult to get subsidies to help pay for it. Even though federal law is clear that states can pay for care that is legally exempt from licensing, many states have moved away from providing child care subsidies to help families pay for care in these smaller, legally unregulated settings.

Second, parents who do want to return to the child care center they used before the pandemic may not be able to. Surveys of providers across the country find that child care centers are facing significant challenges and many have not reopened, some are reopening more slowly, and those that are open have fewer available spots for children than before the pandemic. Their challenges include restrictions on the number of children they can serve and challenges in protecting the health of children and staff, all of which result in higher costs for providers who were already operating close to the margin and are unable to pass these higher costs onto parents.

These realities suggest parents’ uncertainty about being able to return to their prepandemic settings may reflect uncertainty about whether they are still comfortable with their prepandemic setting, whether it is available to them, or both.

Supporting the full range of child care options

To ensure families can access the child care they need to work and ensure their children’s healthy development, federal and state policymakers should focus on supporting parents’ access to child care assistance and a robust supply of care options.

- Help families pay for care: The Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) is the federal-state child care subsidy system that helps families pay for child care. Yet its funding levels only allow it to serve a small fraction (PDF) of those eligible. Increasing funding for the CCDF could help families access child care that meets their needs.

- Ensure child care subsidies can go to the full range of child care settings: States could take steps to identify how their subsidy policies and practices limit parents’ ability to use subsidies for home-based care, and they can look to the several states that still have a sizeable proportion of their children who receive subsidies being served in home-based settings or served in legally unregulated settings as examples.

- Invest in a robust supply of child care options across setting types: Investing in a broad range of financial and in-kind supports for all types of providers—including centers, afterschool providers, licensed family child care homes, and legally unregulated home-based providers—will allow them to meet new health and safety requirements, pay staff decent salaries, and offer health insurance. This should include adjusting subsidy payment rates to support providers’ abilities to meet new health protections and new business models based on serving fewer children. States could target some of these efforts to home-based settings by supporting strategies such as family child care networks (PDF), shared-service models, and other approaches that allow all child care providers to meet new challenges.

In short, the pandemic has wreaked havoc on the supply of child care, both in centers and in the home-based settings that parents increasingly seem to want to use. Ensuring parents can find the care they need, and get help paying for it, is critical in supporting their ability to work and getting our economy back on its feet.

Philip Fisher, Philip H. Knight chair and professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, contributed to this post.

Click here to view the original post.