Effective Tutoring: Out-of-school Time Providers Need To Know What Works

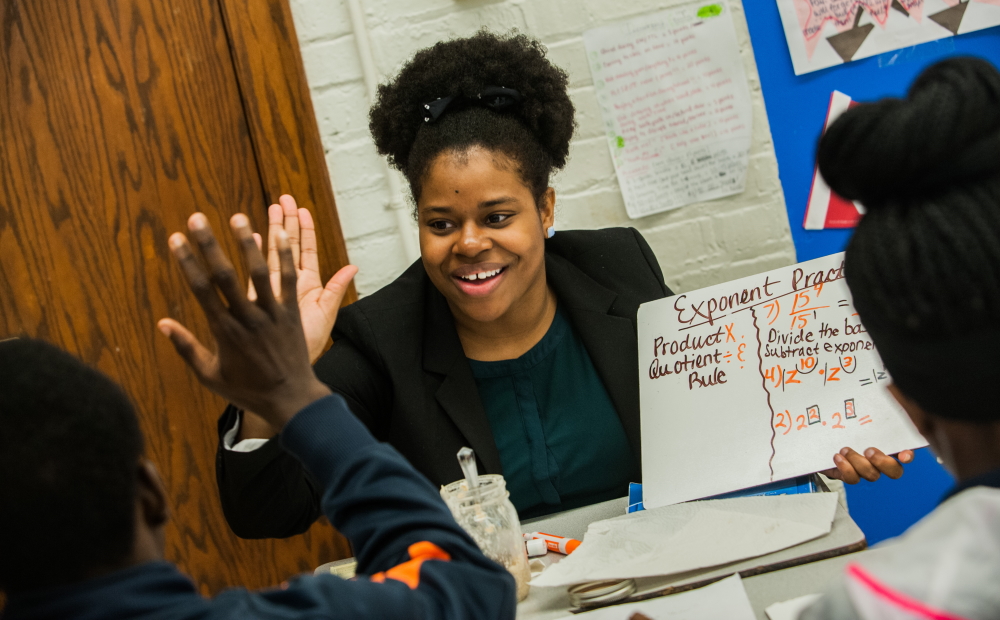

Research shows that high-intensity tutoring is the most effective method to help students who have fallen behind. Here, a trained Saga Education tutor works daily in a group of no more than two students and coordinates closely with classroom teachers.

By Stell Simonton, Reprinted from Youth Today

In the coming months, after-school and summer learning programs will be partnering with schools to address learning loss in the pandemic.

Tutoring will be among the activities that out-of-school time programs may offer — but not all tutoring is created equal.

Kids who are behind need a certain type of tutoring — high-intensity tutoring — to catch up, said Winnie Chan, director of P-12 research at the Education Trust, a research and advocacy nonprofit. She spoke at a March 1 online gathering of the National Summer Learning Association.

“There are a lot of things we can do to really accelerate learning for our students,” she said. A carefully designed high-intensity tutoring program is one of them.

To qualify as high intensity, the tutoring takes place at least three days per week for at least 30 minutes per day in groups no larger than five students, according to a recent review of the research.

“It’s important that the curriculum is at grade level,” Chan said. The work should be aligned with a student’s classwork.

The tutors would ideally be trained teachers, but can also be paraprofessionals, teachers-in-training or well-trained volunteers such as AmeriCorps service members.

Tutors should have ongoing support and training, and the program should build a relationship between the student, their classroom teacher and outside tutor, according to research.

“Positive adult relationships are very important in tutoring,” Chan said.

TUTORS TRAINED, COACHED THROUGHOUT

A recent study at the University of Chicago Education Lab underscored these practices. An in-school math tutoring program for ninth and 10th graders run by the nonprofit Saga Education was successful in bringing students up to grade level. Some students gained the equivalent of 2½ years of math in one academic year. The study disputed claims that high school tutoring could not be done cost-effectively.

Students met each day with their tutor in a group of no more than two students per adult, said John Wolf, associate director of the University of Chicago Education Lab.

“The key thing there is that students have consistent access to their tutors and are able to build the relationship,” he said. “[They] build familiarity and comfort levels with the tutors that they’re working with.”

The daily tutoring was built into the student’s school schedule.

Wolf said that’s possible in after-school or summer learning programs, but “it’s really important to figure out ways to facilitate that consistent engagement.”

A second important ingredient was that tutors had a direct line of communication with the math teachers and departments in the partner schools, Wolf said. Tutors aligned their material with the classroom teacher and would “backfill” skill gaps and offer remedial support, he said.

“All of the material that the tutors were working on was aligned directly with the scope and sequence of the math teachers,” he said.

Another critical ingredient was the training and ongoing coaching of tutors, he said:

“We think that is a key driver of the really large gains that we saw.”

The Saga tutors had a month of training and onboarding before beginning work, ongoing feedback and coaching and were supervised by a site director.

A July 2020 review of 96 studies showed other tutoring programs that stood out:

Reading Recovery, Number Rockets, ROOTS and Match Corps Tutoring. They all fit the high-intensity tutoring model.

In addition, the National Center on Intensive Intervention is a resource for evidence-based tutoring programs.

To access the resource, please click here.