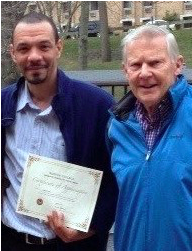

Meet Gil Noam, an expert on trauma informed care

Gil Noam, Ed.D, Ph.D is the founder and director of The PEAR Institute: Partnerships in Education and Resilience at Harvard University and McLean Hospital. The PEAR Institute is a translational center that connects research to practice and is dedicated to serving “the whole child-the whole day.” An associate professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School focusing on prevention and resilience, he trained as a clinical and developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst in both Europe and the United States. Dr. Noam has a strong interest in translating research and innovation to support resilience in youth in educational settings. This interview was originally conducted by Sam Piha

Gil Noam, Ed.D, Ph.D is the founder and director of The PEAR Institute: Partnerships in Education and Resilience at Harvard University and McLean Hospital. The PEAR Institute is a translational center that connects research to practice and is dedicated to serving “the whole child-the whole day.” An associate professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School focusing on prevention and resilience, he trained as a clinical and developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst in both Europe and the United States. Dr. Noam has a strong interest in translating research and innovation to support resilience in youth in educational settings. This interview was originally conducted by Sam Piha

Can you give a brief description of what you mean by “trauma”?

A: This is an excellent question because we tend to use the term quite loosely. Anything that is seriously adverse in a child’s life can be labeled as traumatic and different investigators, clinicians, and educators will have varying definitions of the term. The following points are the ones I use to teach about trauma.

Psychological trauma occurs when overwhelming demands placed upon an individual’s physiological system result in a profoundly felt sense of loss of control, vulnerability, immobilization, betrayal, and heightened sense of evaluation. It is very important to distinguish between “objective trauma” and “subjective trauma.” My definition of “objective trauma” refers to serious events of chronic conditions. For example, an airplane experiencing engine failure is going to be an objective trauma for everyone on board. However, there are many circumstances that come up that are highly traumatizing for one person and less traumatic for another. This then gets us to “subjective trauma.” Chronic parental strife is a good example of an experience that is going to be very unpleasant for any child. But some young people will experience it as highly traumatic, toxic stress, where for others, it’s part of their daily hassle but not necessarily trauma-inducing.

Q: You have said that afterschool programs can be therapeutic for youth. I know that you do not expect afterschool staff to be trained therapists. Can you comment further on what you mean by this?

A: Treating trauma requires a great deal of training and experience. It has taken many years for clinicians to develop and learn the advanced techniques required to treat trauma. it would be unreasonable to expect afterschool staff to perform as experienced therapists.

So what is the role of the teacher and afterschool educator in creating a therapeutic setting? My answer has three components:

- – First, they play a role in helping create trauma-sensitive environments that support both psychological and physical safety. Children who have been traumatized need these kinds of environments, and all students can benefit from them.

- – Second, staff should know the basic manifestations of trauma, such as severe separation anxiety, lack of focus, and high levels of anxiety. These symptoms can have many sources, not all of them are trauma-related for every child. Still, afterschool staff and teachers should be on the lookout for these types of signs (similar to the way they are attentive to rashes, fevers, and other physical symptoms of illness) and should refer children, in collaboration with parents, to services.

- – Lastly, the closeness of mentoring relationships in out-of-school time space can lead children to describe traumatic experiences and can reveal cases of physical or psychological harm. In these cases, laws require educators and youth workers to file an official report – a very difficult process that brings up many feelings in both the child and the adult. Afterschool educators need to be trained on best practices for handling reporting. They also need to learn how to help the child speak to a trained professional. This, of course, is easier for school staff, because there is typically student support staff available during school hours. On the other hand, many afterschool staff do not have access to mental health professionals, so it is essential that we create more access points for them.

Q: You talked about the necessary connection between adversity and resiliency. There are those who say that we underestimate the impact of adversity on the youth we serve. Can you comment?

A: I am very concerned about the return of the education field to a pathology

perspective. Many of us have worked for a long time to change the prevalent paradigm that saw a direct link between trauma and other adversities to psychopathology and later issues. Now, with the advent of new research on toxic stress as well as the work on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), a medical approach to problems is resurfacing. Although these new sciences and ACEs research provide valuable insight, what people tend not to recognize is that most studies show that, even with children who have experienced many difficulties, the majority are adapting well. While difficult experiences have a heightened probability of producing negative outcomes, I truly believe that the significant work on resiliency, which has shown that adversity can actually encourage and expand resiliency (even though we don’t wish adversity on anyone), has to be mentioned and looked at while maintaining concern for the vulnerable child.